|

|

||

|

In neuroscience, context refers to the set of conditions, both internal and external, that influence how the brain processes information, interprets stimuli, and generates responses. It encompasses a broad range of factors that shape neural activity and cognitive function Think of your brain like a detective solving a case. To understand what's going on, the detective needs clues and to look at the environment. In neuroscience, "context" is like those clues and the environment, both inside and outside of you. It includes things happening inside your body, like your mood or if you're hungry, and things happening around you, like the weather or the people you're with. This "context" affects how your brain understands things and reacts. For example, if you hear a loud bang at a fireworks show, your brain might think it's exciting. But if you hear the same bang at home alone at night, your brain might think it's scary. That's because the "context" is different. So basically, "context" in neuroscience means all the things that affect how your brain works and understands the world. It's like putting together a puzzle where your brain uses all the pieces (the context) to see the full picture.

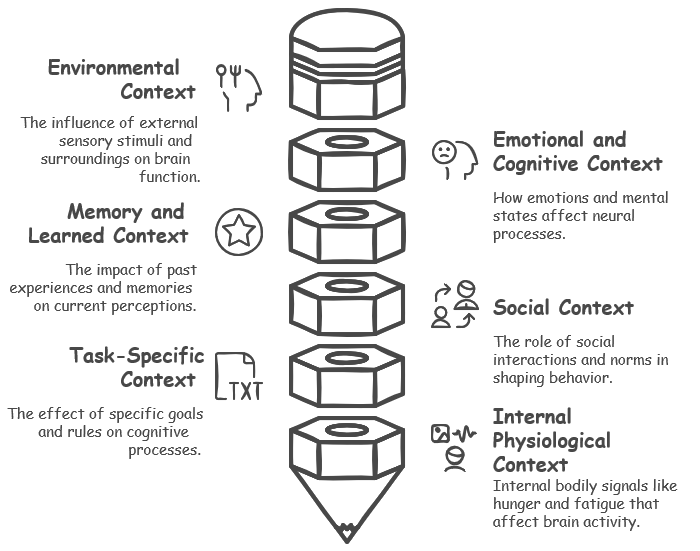

Diversity of the ContextThe concept of context in neuroscience is profoundly diverse, encompassing a broad spectrum of factors that shape how the brain processes information, interprets stimuli, and drives behavior. Context is not a singular entity but a dynamic interplay of various types that include environmental, emotional, cognitive, social, task-specific, and physiological dimensions. Each type of context contributes uniquely to the neural mechanisms underpinning perception, learning, memory, and decision-making. Imagine your brain is like a supercomputer. To understand the world around you, this computer uses information from many different sources. "Context" in neuroscience is like all of this information combined. It's not just one thing, but a mix of many things that affect how your brain works. Think of it like this: where you are, what you see, and the sounds you hear all influence your brain. This is like the computer using its camera and microphone to understand the environment. Also, your emotions, like feeling happy or sad, change how your brain works. This is like the computer checking its internal sensors to see how it's "feeling." Who you're with also matters. Talking with friends or being in a crowd affects your brain differently than being alone. This is like the computer connecting to other computers and sharing information. What you're doing matters too. If you're focused on a task, your brain works differently than when you're relaxed. This is like the computer running different programs depending on the task. Even your body matters! Feeling hungry or tired also changes how your brain works. This is like the computer checking its battery level and other internal systems. All of this information together creates "context." It's like a big puzzle, and your brain uses all the pieces to understand the world and decide how to act. Understanding how all these things work together helps us learn how our brains make us who we are.

Followings are high level components that makes up of a context.

Environmental ContextThink of your brain as always paying attention to the world around you, like a tiny detective gathering clues. This "environmental context" is everything your senses pick up: what you see, hear, smell, touch, and even taste. It's like your brain is taking a picture of your surroundings and using that information to understand what's going on. Your brain has special parts that help you understand where you are and what time it is. For example, it can remember the layout of your house or the time of day based on the sunlight. This helps you make sense of your experiences and remember things better. So, "environmental context" is like a background for your experiences, helping your brain understand the "when" and "where" of everything that happens.

Emotional and Cognitive ContextImagine your brain has a mood ring that changes color with your feelings. This "emotional and cognitive context" is how you're feeling inside—happy, sad, anxious, or focused. Your brain uses these feelings to understand the world around you. It's like your emotions add filters to your experiences. For example, if you're feeling scared, your brain might make you jump at a sudden noise. That's because a part of your brain called the amygdala is working hard to keep you safe. On the other hand, if you're feeling happy, your brain might help you remember good things more easily. So, "emotional and cognitive context" is like your brain's personal assistant, helping it understand how you feel and how to react to the world.

Memory and Learned ContextThink of your brain like a giant library, filled with memories of everything you've ever experienced. This "memory and learned context" is how your past experiences influence how you see the world today. It's like your brain is constantly flipping through the pages of your memories, looking for connections to what's happening right now. For example, if you walk into your childhood home, you might suddenly remember old friends or family gatherings. That's because your brain is linking your current experience to those stored memories. These memories can even affect your emotions and actions. 1 So, "memory and learned context" is like your brain's personal history book, shaping how you understand and react to the present based on your past

Social ContextImagine your brain has a special antenna that picks up signals from the people around you. This "social context" is all about how other people influence your thoughts and actions. It's like your brain is constantly trying to understand the social rules and expectations in any situation. For example, you might act differently at a party with friends than you would at a formal dinner with your family. That's because your brain is picking up on social cues and adjusting your behavior accordingly. Even being around other people can change how your brain makes decisions, like what you choose to eat or how much you're willing to spend. So, "social context" is like your brain's social guide, helping you navigate the complex world of human interaction.

Task-Specific ContextThink of your brain like a chef in a busy kitchen. This "task-specific context" is like the chef's recipe and instructions for a particular dish. It's all about the specific goals and rules you need to follow to complete a task. It's like your brain has a mental checklist for each task, reminding you of what needs to be done and in what order. For example, if you're building a Lego set, your brain will focus on the instructions and the pieces in front of you. A part of your brain called the prefrontal cortex acts like the head chef, making sure you stay focused and follow the plan. So, "task-specific context" is like your brain's task manager, helping you stay organized and achieve your goals.

Internal Physiological ContextImagine your brain is like a car dashboard, with different lights and gauges that tell you how your body is doing. This "internal physiological context" is all about the signals your brain receives from inside your body, like your hunger level, how tired you are, or even if you're getting sick. It's like your brain is constantly checking in with your body to see how things are running. For example, if you're hungry, your brain might start paying more attention to food and make you feel less interested in other things. That's because a part of your brain called the hypothalamus is telling you it's time to eat! Even things like your hormones can affect how your brain works and makes you feel. So, "internal physiological context" is like your brain's internal mechanic, making sure your body and mind are working together smoothly.

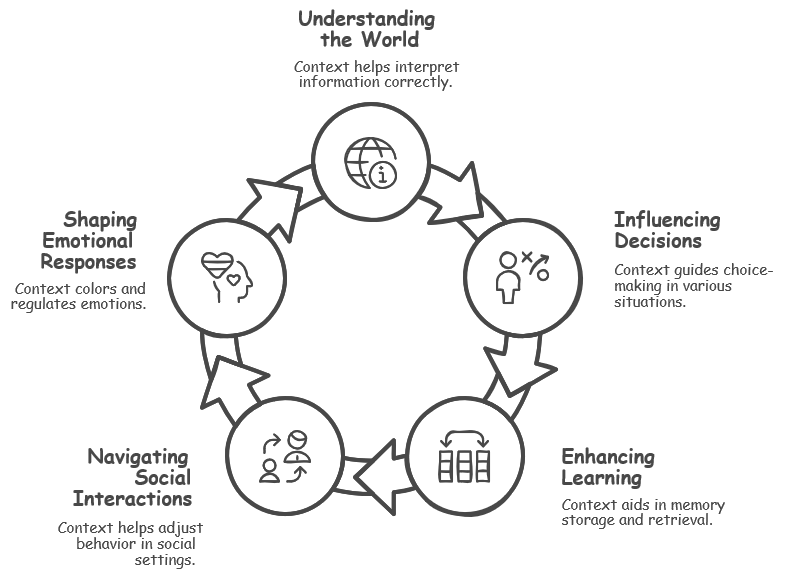

Why Context is important ?Context is like the invisible director of our daily lives, shaping our thoughts, feelings, and actions from moment to moment. It's the reason why you might laugh at a joke with your friends but not with your boss, or why you might feel alert and focused during a work presentation but relaxed and sleepy at bedtime. In essence, context is like the air we breathe – we don't always notice it, but it's essential for our survival and well-being. It helps us adapt to different situations, make smart choices, and interact effectively with the world around us. So next time you're going about your day, take a moment to appreciate the subtle ways context is shaping your experience!

Here's how context plays a role in our everyday lives:

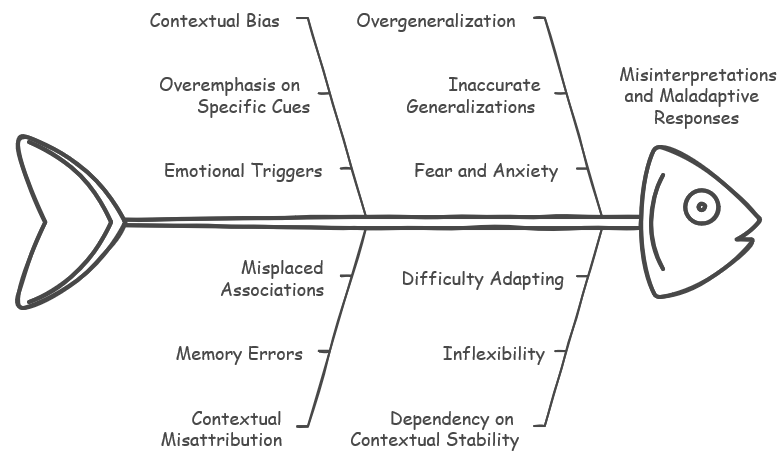

The Hidden Pitfalls of ContextRelying on context for neural processing and decision-making offers adaptability and efficiency, but it also comes with several pitfalls. These challenges arise due to the brain's dependency on contextual cues, which can lead to misinterpretations or maladaptive responses in certain situations. Think of your brain like a detective who uses clues to solve a case. Using "context" is like relying on those clues to understand what's happening. It's usually a good thing, helping your brain work quickly and efficiently. But sometimes, relying too much on clues can lead to mistakes. Imagine you're walking down the street and see someone frowning. Because of the context – their facial expression – you might assume they're angry or upset. But what if they're just concentrating really hard on something, or maybe they have a headache? Relying only on that one contextual clue – the frown – could lead you to misinterpret their true feelings. Similarly, our brains sometimes make incorrect assumptions based on context. We might misinterpret someone's words or actions because we're missing important information. Or we might react in a way that's not helpful because we're relying on past experiences that aren't relevant to the current situation. So, while context is important for our brains, it's also important to be aware of its limitations. Just like a good detective, we need to be careful about jumping to conclusions and consider all the possibilities before making a decision.

Contextual BiasImagine your brain has a spotlight that it shines on the world around you. This spotlight helps you focus on what's important, but it can also create shadows, hiding things that might be crucial to understand the whole picture. This is similar to "contextual bias" – where your brain might focus too much on certain pieces of information while ignoring others, leading to skewed judgments. For example, imagine you're walking home alone at night and hear a sudden noise. Your brain, already primed for potential danger in the darkness, might immediately jump to the conclusion that there's a threat, making your heart race and your senses heighten. This is your amygdala – the brain's alarm system – kicking into overdrive. However, the noise might just be a cat knocking over a trash can. Because your brain prioritized the "danger" context, it overreacted to a harmless situation. This bias can show up in many ways. If you've had a bad experience with a particular breed of dog, you might feel fear every time you encounter a dog of that breed, even if it's friendly and playful. Or, if you're used to people being dishonest with you, you might misinterpret a sincere compliment as insincere. Contextual bias can be helpful in situations where quick decisions are needed, but it can also lead to misjudgments, unfair assessments, and missed opportunities. It's like looking at a picture with a flashlight – you might see some details clearly, but you might miss other important parts of the image lurking in the shadows.

Contextual MisattributionThink of your brain like a filing cabinet, with different drawers for storing memories and experiences. "Contextual misattribution" is like accidentally putting a file in the wrong drawer. You might remember the information, but you've mixed up the details, leading to confusion and mistakes. Imagine you're trying to remember a funny joke someone told you. You might remember the joke itself, but misremember who told it to you or where you heard it. This is a common example of contextual misattribution – your brain has correctly recalled the information, but it's attached it to the wrong context. This can happen in more serious situations too. For example, you might misremember details of an important conversation, leading to misunderstandings or disagreements. Or you might associate a feeling of anxiety with the wrong place or situation, leading to unnecessary fear or avoidance. Contextual misattribution can even distort your memories over time. Like a game of telephone, each time you recall a memory, it can change slightly, and if you keep retrieving it in the wrong context, those changes can become more significant. Essentially, contextual misattribution is like misplacing the pieces of a puzzle. You might have all the right pieces, but if they're not in the right places, the picture won't make sense. This can lead to confusion, errors in judgment, and even social awkwardness. So, it's important to be mindful of how we store and retrieve our memories, ensuring that we keep the right information in the right context.

OvergeneralizationImagine your brain has a "shortcut" button that helps it quickly apply what it has learned in one situation to new situations. This can be very useful for learning and adapting to the world, but sometimes, this shortcut can lead to "overgeneralization" – where your brain applies a rule or expectation to situations where it doesn't actually fit. Think of it like this: you touch a hot stove and burn your hand. Your brain quickly learns that hot stoves are dangerous and should be avoided. That's a helpful generalization! But what if your brain overgeneralizes this rule and makes you afraid of all stoves, even cold ones, or even other kitchen appliances? That's where overgeneralization can become a problem. This can happen with emotional responses too. Let's say you had a negative experience public speaking in school. Your brain might overgeneralize this experience and make you feel anxious about any kind of public speaking, even giving a toast at a friend's wedding or presenting a project at work, even though these situations are very different. Overgeneralization can lead to a variety of challenges, including phobias, anxiety disorders, and even prejudice. It's like painting everything with the same brush, even though different situations require different approaches. While our brains are wired to make generalizations, it's important to recognize when those generalizations are inaccurate or unhelpful and to be willing to update our understanding based on new experiences.

Dependency on Contextual StabilityImagine your brain is like a GPS system that helps you navigate the world. It learns the best routes and landmarks to get you where you need to go. But what happens when there's construction, a detour, or a road closure? If your GPS is too reliant on the usual route, it might struggle to adapt and find a new way. This is similar to how our brains can become dependent on "contextual stability" – we learn and perform best in familiar, predictable environments. Think about someone who thrives in a quiet library where they can focus on their studies. If they suddenly have to work in a bustling coffee shop with lots of noise and distractions, their usual strategies for concentration might not work as well. Their brain is used to a specific set of contextual cues – the quiet, the stillness – and without those cues, they struggle to adapt. This dependency can affect us in many ways. A musician who is used to performing on a specific stage might feel uncomfortable and perform less well in a new venue. An athlete who trains in a controlled environment might struggle to perform in a game with unpredictable weather and a noisy crowd. While having routines and predictable environments can be helpful, becoming too reliant on them can make us inflexible and less able to cope with change. It's like having a map that only shows one route – if that route is blocked, you're lost. Developing cognitive flexibility – the ability to adapt to new situations and update our strategies – is essential for navigating the ever-changing world around us.

Ambiguous or Conflicting ContextsImagine your brain is like a detective trying to solve a case with conflicting witness statements. When contexts are ambiguous or conflicting, it's like getting clues that point in different directions, making it difficult to determine the truth. Think about sarcasm. Someone might say "That's just great!" with a sarcastic tone of voice and a frown. Their words suggest something positive, but their tone and facial expression suggest the opposite. This creates an ambiguous context where your brain has to weigh conflicting information. Did they really mean it was great, or were they being sarcastic? This kind of ambiguity happens all the time in our daily lives. You might receive an email that seems friendly but has an underlying tone of annoyance. Or you might encounter a social situation where the spoken rules are different from the unspoken rules. When faced with ambiguous or conflicting contexts, our brains have to work harder to make sense of the situation. This can lead to confusion, misinterpretations, and even social missteps. We might misinterpret a joke as an insult, or we might miss a subtle cue that someone is feeling uncomfortable. It's like trying to assemble a puzzle where some of the pieces seem to fit in multiple places. To navigate these situations successfully, we need to be attentive to all the contextual cues, consider different perspectives, and be willing to ask for clarification when needed. Just like a good detective, we need to carefully examine all the evidence before reaching a conclusion.

Contextual OverloadImagine your brain is like a computer with many programs running at the same time. "Contextual overload" is like opening too many tabs and applications, pushing your computer's processing power to its limits. It can make your computer slow down, freeze, or even crash. Similarly, our brains can become overwhelmed when we have to process too much contextual information at once. Think about trying to have a conversation in a crowded, noisy room while also trying to keep track of your belongings and navigate your way through the crowd. Or imagine a student trying to study for an exam while also responding to text messages, listening to music, and keeping an eye on social media. Each of these tasks requires attention and processing power, and when your brain is bombarded with too many demands simultaneously, it can lead to "contextual overload." This can result in:

Just like a computer needs to close some programs to free up memory, our brains need to prioritize and filter information to avoid overload. This is why it's important to create environments that support focus and minimize distractions, especially when we're engaged in complex tasks. Taking breaks, practicing mindfulness, and learning to prioritize tasks can also help us manage contextual overload and keep our brains functioning at their best.

Pathological Context DependenceImagine your brain is like a musical instrument that needs to be properly tuned to play the right notes. In some neurological or psychiatric conditions, this tuning can be off, making it harder to process context accurately. This is what we mean by "pathological context dependence." For example, individuals with autism spectrum disorder often thrive on routine and predictability. Changes in context, like a different schedule or an unexpected event, can be very distressing and make it difficult for them to adapt. It's like their brains are playing a familiar song, and any change in the rhythm or melody throws them off. On the other hand, individuals with schizophrenia might experience context in a distorted way. Their brains might misinterpret sensory information or social cues, leading to hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that aren't there) or delusions (believing things that aren't true). It's like their brains are playing a different song altogether, one that doesn't match the reality around them. Other conditions can also affect how the brain processes context. People with anxiety disorders might be overly sensitive to threat cues in their environment, while those with depression might have a negative bias, interpreting neutral situations as negative. Pathological context dependence can significantly impact daily life. It can make it harder to learn, socialize, make decisions, and cope with stress. It's like trying to play a beautiful piece of music on an out-of-tune instrument – the potential is there, but the result is distorted. Understanding how these conditions affect context processing is crucial for developing effective treatments and support strategies

Cultural and Social Context MisalignmentImagine your brain is like a translator that helps you understand the language and customs of different cultures. "Cultural and social context misalignment" is like having a translator that's not quite fluent, leading to misunderstandings and misinterpretations. Think about greetings. In some cultures, a firm handshake is the standard greeting, while in others, a bow or a kiss on the cheek is more common. If someone from a handshake culture meets someone from a bowing culture, they might misinterpret the lack of a handshake as coldness or disinterest, even though it's simply a different cultural norm. This misalignment can occur in many situations. Direct eye contact might be seen as respectful in one culture but disrespectful in another. The use of humor, personal space, and even the way people express emotions can vary widely across cultures. When these cultural contexts clash, it can lead to social friction, stereotyping, and even exclusion. People might misjudge each other's intentions, feel uncomfortable or offended, and struggle to build relationships. It's like trying to have a conversation with someone speaking a different language – without a good translator, communication can break down easily. Being aware of cultural and social context misalignment is crucial for fostering understanding and inclusivity. It requires us to be open-minded, curious about other cultures, and willing to adjust our expectations. Just like a good translator, we need to learn the nuances of different cultural "languages" to communicate effectively and build bridges across cultures.

Vulnerability to ManipulationImagine your brain is like a ship navigating the ocean. It uses its instruments and charts to steer a safe course and reach its destination. But sometimes, external forces like strong currents or misleading beacons can push the ship off course. "Vulnerability to manipulation" is like encountering these misleading signals that can influence your direction without you realizing it. One way this happens is through the manipulation of context. Think of skilled marketers and influencers as cunning pirates who know how to manipulate the navigational tools of your mind. They might use clever packaging, catchy slogans, or celebrity endorsements to create an irresistible allure around their product, making you feel like you need it even if you don't. For example, a fast-food commercial might use images of happy families and mouthwatering food to create a positive association with their brand. Or a social media influencer might showcase a luxurious lifestyle to make you believe that buying their products will bring you happiness and success. This manipulation can be subtle and persuasive. It plays on our emotions, our insecurities, and our desire for belonging. It can lead us to buy things we don't need, support causes we don't fully understand, or even adopt beliefs that are harmful. It's like those pirates subtly changing the readings on your compass or charting a course towards treacherous waters. You might think you're in control, but your decisions are being subtly influenced by external forces. Protecting yourself from manipulation requires critical thinking, media literacy, and a healthy dose of self-awareness. It's like having a skilled navigator on board who can identify those misleading signals and keep your ship on the right course. By questioning information, considering different perspectives, and being mindful of our own biases, we can navigate the sea of information safely and reach our own true destination.

Overreliance on Context for Memory RetrievalImagine your brain is like a treasure chest filled with valuable memories and knowledge. But this chest has a special lock that requires the right key to open it. That key is "context." "Overreliance on context for memory retrieval" is like having a chest full of treasure but only being able to open it in one specific location. Think about studying for an exam. You spend hours in the library, surrounded by books and the quiet hum of concentration. You learn the material thoroughly, feeling confident in your knowledge. But then, when you sit down to take the exam in a different room with different surroundings, you suddenly find yourself struggling to recall the information. The context has changed, and your brain is having trouble finding the right "key" to unlock those memories. This happens because our brains often associate information with the environment in which it was learned. The sights, sounds, smells, and even the emotions we experience during learning become linked to the information itself. When we return to that same context, those cues help trigger the retrieval of the memories. But when the context changes significantly, those cues are missing, and our brains have to work harder to access the information. This is why you might remember a childhood friend's name when you visit your old neighborhood, or why a familiar song can trigger a flood of memories from the past. Overreliance on context for memory retrieval can limit our ability to apply knowledge flexibly. It's like having a map that only works in one city – you can navigate that city perfectly, but you'll be lost anywhere else. To truly master knowledge and skills, we need to be able to access them in a variety of contexts. Techniques like spaced repetition, active recall, and teaching the information to others can help strengthen memory and make it less dependent on specific cues.

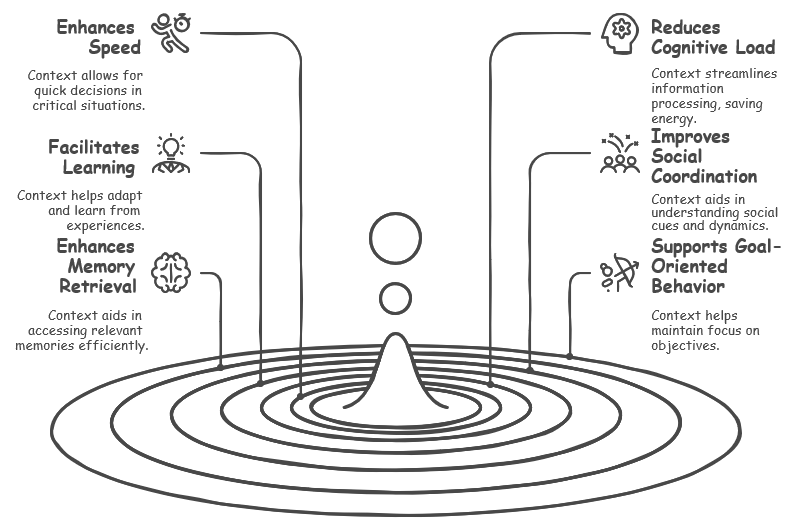

The Evolutionary Advantage of Context: Why Our Brains Embrace It Despite the RisksThe human brain evolved to rely heavily on context despite its pitfalls because of the adaptive advantages it offers. The tendency to use context enhances survival and efficiency, far outweighing the risks of occasional errors. It's like our brains have developed a shortcut that says, "If it worked before in a similar situation, it's probably a good bet now." This allows us to make quick decisions and navigate a complex world without getting bogged down in analyzing every detail. Think of our ancestors trying to survive in the wild. If they saw a rustling in the bushes, their brains would quickly use context – the time of day, the environment, past experiences – to determine if it was a predator or just the wind. A quick decision to flee, even if it was a false alarm, was far better than a slow, calculated decision that might end with them becoming dinner. This "good enough" approach to decision-making, relying heavily on context, has been favored by evolution because it prioritizes speed and efficiency. Sure, it might lead to occasional mistakes, but those mistakes are often less costly than the time and energy it would take to analyze every situation perfectly. It's like choosing between two paths in the jungle. One path is well-worn and familiar, but might have a few hidden traps. The other path is completely unknown and might be safer, but it would take much longer to explore. Our brains, shaped by evolution, often choose the familiar path, even with the risk of a few missteps. So, while context can sometimes lead us astray, it's ultimately a powerful tool that has helped humans survive and thrive. It allows us to adapt quickly, make efficient decisions, and navigate a world full of uncertainties. It's a trade-off that sacrifices perfection for practicality, and it's a key part of what makes us human.

Enhances Decision-Making SpeedImagine you're an early human walking through a dense forest. You hear a twig snap behind you. Do you stop to carefully analyze the situation, or do you instantly react and run? In the wild, hesitation could be fatal. That's where context comes in, acting like your brain's rapid response system. Your brain instantly takes in the context: the sound of the twig, the dense foliage, the fact that predators might be lurking. It draws on past experiences and innate instincts, triggering a surge of adrenaline and an urge to flee. This quick decision, based on context, could save your life, even if it turns out that the twig was just snapped by a falling branch. In our modern lives, we might not face life-or-death decisions in the wilderness, but the need for quick thinking remains. Context helps us navigate busy traffic, respond to sudden emergencies, and make split-second choices in sports or competitive environments. Think of a doctor in an emergency room. They don't have time to ponder over every detail when a patient arrives with critical injuries. They rely on their training, experience, and the immediate context – the patient's symptoms, vital signs, and the urgency of the situation – to make rapid decisions that can save lives. So, while context can sometimes lead to errors, its ability to enhance decision-making speed is a crucial survival advantage. It allows us to react quickly in dynamic situations, maximizing our chances of survival and success in a world that often demands swift action.

Reduces Cognitive LoadImagine your brain is like a powerful search engine, constantly sifting through a vast amount of information. But just like a computer, your brain has limited processing power. "Reducing cognitive load" is like using smart filters and shortcuts to avoid overloading your brain's search engine. Your brain is a hungry organ, consuming a significant portion of your body's energy. To conserve energy and avoid mental fatigue, it relies on context to streamline information processing. Think of walking into a crowded room. Your brain doesn't need to analyze every single face in detail to find your friend. It uses contextual cues like their hair style, clothing, or the way they move to quickly identify them, saving precious mental energy. This applies to many everyday tasks. When you're driving, you don't consciously process every detail of the road, the cars around you, and the scenery. Your brain filters out irrelevant information, focusing on the essential cues for safe navigation. Context also helps us make quick judgments and decisions without getting bogged down in endless analysis. If you're choosing what to eat for lunch, you don't need to research the nutritional value of every item on the menu. You can use context – your preferences, dietary needs, and past experiences – to make a satisfying choice efficiently. So, by filtering out irrelevant details and prioritizing important information, context helps your brain operate more efficiently. It's like having a smart assistant that organizes your mental workspace, allowing you to focus on what matters most without wasting precious energy.

Facilitates Learning and AdaptationImagine your brain is like a detective constantly searching for clues and patterns to understand the world. "Facilitating learning and adaptation" is like your brain becoming a master detective, using context to connect the dots and predict what might happen next. Think of our ancestors encountering a new plant for the first time. They might try it, and if it makes them sick, their brains quickly associate that plant with the negative experience. The context – the plant's appearance, smell, location – becomes a warning sign, preventing them from consuming it again. This ability to learn from experience and adapt our behavior is crucial for survival. Context helps us learn in countless ways. A child learns that touching a hot stove causes pain, so they avoid doing it again. A student learns that certain study habits lead to better grades, so they repeat those habits. A musician learns that practicing regularly improves their performance, so they make practice a priority. Context also helps us adapt to new situations. If you move to a new city, you quickly learn the layout, the transportation system, and the social norms. You adapt your behavior based on the context, making new friends and navigating your new environment with increasing ease. It's like your brain is constantly building a map of the world, with each experience adding new landmarks and pathways. Context helps connect these landmarks, creating a richer and more detailed map that guides our actions and decisions. This ability to learn and adapt is what allows us to thrive in a constantly changing world.

Improves Social CoordinationImagine your brain is like a radio receiver, constantly tuning in to the signals and cues from the people around you. "Improving social coordination" is like fine-tuning your receiver to clearly understand the messages and emotions being conveyed, allowing for smoother interactions and stronger connections. Humans are social creatures, and our survival has always depended on our ability to cooperate and work together. Context plays a vital role in this social coordination. It helps us understand the unspoken rules, expectations, and dynamics within our social groups. Think about a conversation with a friend. You're not just listening to their words, but also paying attention to their tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language. These contextual cues provide valuable information about their emotional state and intentions, allowing you to respond appropriately and build a stronger connection. Context also helps us navigate complex social situations. Imagine attending a formal dinner party. You use contextual cues – the dress code, the table setting, the behavior of others – to understand the expected etiquette and adjust your behavior accordingly. This helps you avoid social faux pas and maintain harmonious relationships. In a work environment, understanding the context is crucial for effective teamwork. Recognizing the roles, responsibilities, and communication styles of your colleagues allows you to collaborate efficiently and achieve shared goals. So, by enhancing our ability to read social cues, understand social dynamics, and adapt our behavior accordingly, context strengthens our social bonds and improves cooperation. It's like having a social GPS that guides us through the complexities of human interaction, fostering understanding, empathy, and successful collaboration.

Enhances Memory RetrievalImagine your brain is like a vast library filled with countless books, each representing a memory or piece of knowledge. "Enhancing memory retrieval" is like having a librarian who knows exactly where to find the specific book you need at any given moment. That librarian is "context." Think about trying to build a fire in the wilderness. Your brain doesn't need to recall every fact you've ever learned about fire – the chemical composition of wood, the history of fire-making tools, or the physics of combustion. Instead, it focuses on the relevant information within the context of your current situation: how to gather dry tinder, how to arrange kindling, and how to create a spark. Context acts as a filter, helping your brain prioritize and retrieve the most useful information for a given situation. It's like having a mental search engine that automatically narrows down the results based on your current needs and environment. This applies to many aspects of our lives. When you're cooking a meal, you don't need to remember every recipe you've ever read. You focus on the specific dish you're making and the ingredients at hand. When you're having a conversation, you don't need to recall every word you've ever learned. You access the vocabulary and grammar relevant to the topic and the social context. So, by providing cues and associations, context helps your brain efficiently retrieve the most pertinent information from its vast storehouse of memories. It's like having a personalized library catalog that guides you to the exact knowledge you need, when you need it, making your brain a more effective and adaptable tool for navigating the world.

Supports Goal-Oriented BehaviorImagine your brain is like a highly skilled archer aiming for a target. "Supporting goal-oriented behavior" is like having a steady hand and a keen eye that help you focus on the bullseye and ignore the distractions that might throw off your aim. Context acts like a mental spotlight, illuminating the path towards your goals and filtering out irrelevant information. Think of a hunter tracking prey through a dense forest. Their senses are bombarded with stimuli – the rustling of leaves, the chirping of birds, the scent of damp earth. But their brain prioritizes the most relevant cues – the tracks on the ground, the snapping of twigs, the glimpse of movement in the undergrowth – allowing them to stay focused on their goal. This ability to prioritize and filter information is crucial for achieving any goal, whether it's hunting for food, completing a work project, or mastering a new skill. Context helps us stay on track by highlighting the most important information and suppressing distractions. Imagine you're writing an essay. Your brain needs to focus on the topic at hand, the structure of your argument, and the flow of your writing. Context helps you filter out irrelevant thoughts, memories, or external distractions that might derail your train of thought. Or think of an athlete preparing for a competition. Their brain needs to focus on their technique, their strategy, and their opponent's movements. Context helps them block out the noise of the crowd, the pressure of the moment, and any self-doubt that might hinder their performance. So, by guiding our attention and filtering out distractions, context helps us stay focused on our goals and achieve success. It's like having a mental compass that keeps us oriented towards our desired destination, even when the path is challenging or filled with distractions.

Facilitates Cognitive FlexibilityImagine your brain is like a toolbox filled with different tools for different tasks. "Facilitating cognitive flexibility" is like having the ability to quickly switch between tools depending on the situation, allowing you to adapt and overcome any challenge. Context is like the instruction manual for your brain's toolbox, telling you which tool is best suited for each task and environment. Think of our ancestors adapting to the changing seasons. In the summer, they might have relied on gathering fruits and berries, while in the winter, they might have shifted to hunting or foraging for roots and nuts. Their brains used context – the weather, the availability of resources, the presence of predators – to adjust their strategies and ensure their survival. This cognitive flexibility is essential for navigating a complex and ever-changing world. It allows us to:

So, by enabling us to switch between different mental tools and strategies, context empowers us to adapt, learn, and thrive in a dynamic world. It's like having a mental Swiss Army knife, equipped with a versatile set of skills to tackle any challenge that comes our way.

Enables Complex Social StructuresImagine your brain is like a conductor leading an orchestra. "Enabling complex social structures" is like the conductor guiding each musician to play their part in harmony, creating a beautiful and intricate symphony of human interaction. Context acts as the musical score, providing the structure and guidelines for social behavior. It allows us to understand and navigate the intricate web of relationships, hierarchies, and cultural norms that make up our societies. Think of a traditional wedding ceremony. Each participant understands their role and the sequence of events thanks to shared cultural context. The bride and groom, the families, the officiant, and the guests all follow established customs and traditions, creating a sense of unity and shared purpose. Context also helps us interpret and respond to social cues in everyday interactions. We learn to adjust our behavior depending on the social setting, the people we are with, and the unspoken rules of etiquette. This allows us to build trust, maintain harmony, and navigate complex social hierarchies. Imagine a workplace environment. Context helps us understand the company culture, the communication styles of our colleagues, and the expectations for professional conduct. This allows us to collaborate effectively, resolve conflicts constructively, and contribute to a positive and productive work environment. So, by providing a framework for social behavior and enabling us to understand and respond to social cues, context supports the development and maintenance of complex social structures. It's like the invisible glue that holds societies together, allowing us to cooperate, communicate, and build thriving communities.

Promotes Risk MitigationImagine your brain is like a sophisticated security system, constantly scanning for potential threats and vulnerabilities. "Promoting risk mitigation" is like having advanced sensors and alarms that help you anticipate and avoid danger before it strikes. Context acts as your brain's early warning system, providing crucial information about potential risks and guiding you towards safer choices. Think of seeing dark storm clouds gathering on the horizon. Your brain, drawing on past experiences and knowledge of weather patterns, recognizes the potential danger and prompts you to seek shelter, reducing your risk of being caught in a storm. This ability to assess and mitigate risk is essential for survival in a world full of potential hazards. Context helps us:

So, by enhancing our ability to perceive, interpret, and respond to potential threats, context helps us navigate a world full of uncertainties and make safer choices. It's like having a personal risk management consultant, guiding us towards actions that minimize danger and maximize our chances of safety and well-being.

Drives Creativity and InnovationImagine your brain is like a fertile garden where ideas blossom and creativity flourishes. "Driving creativity and innovation" is like nurturing that garden, providing the rich soil and optimal conditions for new ideas to take root and grow. Context acts as the fertilizer, enriching our minds with diverse perspectives and inspiring unexpected connections. It allows us to draw parallels between seemingly unrelated concepts, sparking innovation and problem-solving. Think of our ancestors observing the natural world. They might have noticed how birds use their wings to fly, how fish use their fins to swim, or how plants use their roots to anchor themselves. By applying these observations to different contexts, they could invent tools for hunting, fishing, or farming, sparking innovation and progress. This ability to connect ideas across different domains is essential for creativity and problem-solving. Context helps us:

So, by fostering connections, broadening perspectives, and encouraging flexible thinking, context fuels creativity and innovation. It's like providing our minds with a diverse palette of ideas, allowing us to paint a masterpiece of ingenuity and progress.

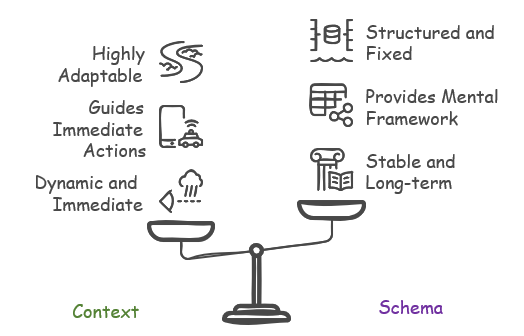

Context vs. Schema: Unraveling the Brain's Dynamic Framework for Understanding the WorldContext and schema are like two intertwined threads that weave together the fabric of our understanding. Think of context as the "stage" and schema as the "play." Context is the immediate environment and situation you find yourself in—the specific set of circumstances surrounding you at any given moment. This includes the physical location, the people present, the time of day, and your current activity. It's like the stage setting for your experiences. Schema, on the other hand, is the mental framework or blueprint you use to interpret and interact with that context. It's the collection of knowledge, beliefs, and expectations you've built up over time through your experiences and learning. Think of it as the script for the play, guiding your actions and responses. For example, imagine you're attending a birthday party. The context is the specific party itself—the location, the decorations, the people attending, the music playing. Your schema for "birthday party" might include expectations about cake, presents, games, and social interaction. This schema helps you understand what's happening and how to behave appropriately in that context. These two concepts work together dynamically. Each new experience in a specific context adds to and refines your schema. If this birthday party has a unique theme or unexpected activities, your "birthday party" schema will be updated with this new information. At the same time, your existing schemas influence how you perceive and interpret the context. If you have a positive schema for birthday parties, you're more likely to notice the joyful atmosphere and friendly interactions. While context is specific to the immediate situation, schema is more general and applies to a broader category of experiences. Context is constantly changing, while schema is more stable, although it can be updated over time. Essentially, context is external and focuses on the environment, while schema is internal and focuses on mental representations. Context and schema are like two sides of the same coin. Context provides the raw material for our experiences, while schema provides the tools for understanding and interacting with that material. They work together seamlessly, allowing us to navigate a complex world with efficiency and flexibility.

DefinitionContext is the immediate set of circumstances surrounding you right now. It's like the current weather conditions—sunny or rainy, hot or cold, windy or calm. It changes from moment to moment and influences how you experience the world in that specific instance. Just like dim lighting in a room might make colors appear muted, the context of a situation shapes your perception and actions. Schema, on the other hand, is the broader pattern of your experiences and knowledge. It's like the climate of a region—the overall trends and expectations based on long-term observations. Your schema for a "classroom," for example, might include expectations about desks, a blackboard, and a teacher, based on your past experiences with classrooms. This schema provides a framework for understanding new classrooms you encounter, even if they have slight variations. Here's a key difference: context is dynamic and ever-changing, like the weather. Schema is more stable and enduring, like the climate, although it can be updated and refined over time with new experiences. Essentially, context provides the immediate backdrop for your experiences, while schema provides the long-term framework for interpreting those experiences. Both are essential for navigating the world and making sense of the information around us.

Temporal NatureThink of it this way: context is like a snapshot, while schema is like a photo album. Context captures a fleeting moment in time. It's like a snapshot of your current surroundings and circumstances. Just as the mood of a conversation can change instantly when someone new enters the room, context is ephemeral and constantly shifting. It's tied to the "here and now" and influences your immediate perceptions and actions. Schema, on the other hand, is a collection of experiences and knowledge accumulated over time. It's like a photo album filled with memories and lessons learned. Just as a child gradually develops a schema for "animals" by encountering different creatures and learning about their characteristics, schemas are built gradually through repeated exposure and learning. They provide a lasting framework for understanding the world, even as specific contexts change. Here's a key difference: context is temporary and specific to the present situation, like a snapshot that captures a single moment. Schema is enduring and represents a broader understanding, like a photo album that tells a story over time. Essentially, context provides the fleeting backdrop for your experiences, while schema provides the enduring framework for organizing and interpreting those experiences. Both are vital for navigating the world and making sense of the constant flow of information.

FunctionThink of it this way: context is like a GPS guiding you on a specific trip, while schema is like a mental map of the world. Context helps you navigate the immediate situation by providing real-time information and guidance. It's like using a GPS to get to a new destination. The GPS considers your current location, traffic conditions, and road closures to provide the most efficient route. Similarly, when you decide to wear a coat because it's snowing outside, you're using context—the current weather conditions—to guide your decision-making. Schema, on the other hand, provides a broader understanding of how the world works. It's like having a mental map that shows you the general layout of a city, including major landmarks and common routes. This map doesn't tell you exactly how to get from point A to point B, but it gives you a framework for understanding the city's structure and making informed decisions about navigation. Similarly, when you expect a waiter to bring a menu when you sit at a restaurant, you're relying on your schema for "restaurants" to guide your expectations and behavior. Here's a key difference: context guides your actions in the immediate present, like a GPS providing turn-by-turn directions. Schema provides a broader framework for understanding and predicting the world, like a mental map that helps you orient yourself in unfamiliar territory. Essentially, context helps you adapt to the specific circumstances of the moment, while schema helps you make sense of the world in a more general way. Both are crucial for navigating the complexities of life and making efficient decisions.

Neural BasisThink of it this way: context is like the brain's "on-the-fly" navigation system, while schema is like its "long-term memory" storage and retrieval system. Context engages brain regions that are responsible for processing immediate information and adapting to the current situation. It's like having a dedicated navigation system in your car that constantly updates its route based on real-time traffic, road conditions, and your destination. Brain regions like the hippocampus (which processes spatial information), the prefrontal cortex (which handles decision-making and flexible behavior), and the amygdala (which processes emotions) work together to assess the context and guide your actions. For example, in a conversation, your prefrontal cortex uses contextual cues like the other person's tone of voice and body language to adjust your responses and maintain a smooth flow of interaction. Schema, on the other hand, relies on brain regions that store and retrieve long-term knowledge and memories. It's like having a vast library in your brain, with different sections for different types of information. The medial prefrontal cortex, involved in social cognition and understanding others, and the default mode network, which is active when we're not focused on a specific task and tend to daydream or reflect on past experiences, play a key role in accessing and applying schemas. For example, when you navigate a formal dinner, your brain retrieves stored knowledge about cultural norms and etiquette from these regions to guide your behavior. Here's a key difference: context engages brain regions that are active in processing immediate information and adapting to the current environment, while schema engages regions involved in retrieving and applying stored knowledge and experiences. Essentially, context is like the brain's "online" processing system, while schema is like its "offline" knowledge base. Both systems work together seamlessly, allowing us to navigate the world effectively, make sense of our experiences, and interact with others smoothly.

FlexibilityThink of it this way: context is like a flowing river, while schema is like the riverbed. Context is constantly changing and adapting to the environment. Like a river that twists and turns, responding to the contours of the land, context is fluid and responsive. It shifts with the current situation, the people involved, and the specific stimuli present. For instance, a joke that's hilarious among close friends might be inappropriate at a formal work event. Recognizing this shift in context demonstrates flexibility in social awareness. Schema, on the other hand, provides a more stable foundation. Like the riverbed that guides the flow of water, schema is relatively fixed, though it can gradually change over time. It's based on accumulated knowledge and experiences, providing a structure for understanding the world. However, just as a riverbed can be reshaped by erosion or shifts in the landscape, schemas can evolve with new learning and experiences. For example, your schema about technology might have been limited to computers and smartphones, but learning about the advancements in artificial intelligence expands and updates that schema. Here's a key difference: context is highly adaptable and responsive to the immediate situation, like a river adjusting its course. Schema is more structured and resistant to change, like a riverbed providing a stable foundation, though it can be modified over time. Essentially, context allows for quick adjustments and nuanced interpretations, while schema provides a stable framework for understanding the world. Both are crucial for navigating the complexities of life, with context providing the flexibility to adapt to the moment and schema offering the structure to make sense of it all.

Interaction/InterplayThink of it this way: context and schema are like dancers engaged in an intricate tango. They move together, constantly influencing and shaping each other. Context leads, providing the steps and rhythm, while schema follows, interpreting and responding to the lead. Context informs schema: Just as a new dance move can be incorporated into a dancer's repertoire, new contexts provide the raw experiences that shape and modify our schemas over time. Imagine traveling to a new country with unfamiliar customs and landscapes. This experience expands your understanding of what a "vacation" can be, adding new dimensions to your existing schema. Schema influences context: Just as a dancer's style and skill influence how they interpret and execute a dance move, our schemas shape how we perceive and react to contexts. If you have a schema about "danger" that's been shaped by past experiences, you might be more attuned to contextual cues like dark alleys or loud noises, interpreting them as potential threats. This interplay is continuous and dynamic. Each new context we encounter provides an opportunity to refine our schemas, and our schemas, in turn, influence how we perceive and respond to those contexts. It's a constant feedback loop, shaping our understanding of the world and guiding our actions. Essentially, context and schema are partners in a continuous dance of learning and adaptation. Context provides the steps, and schema provides the interpretation and style. Together, they create a harmonious flow of understanding and action, allowing us to navigate the complexities of life with grace and efficiency.

Errors and PitfallsThink of it this way: context errors are like misreading a signpost, while schema errors are like using an outdated map. Both can lead you astray, but in different ways. Context errors happen when you misinterpret or overemphasize the immediate cues in your environment. It's like misreading a signpost and taking a wrong turn. For example, imagine someone waving their hand dismissively. You might misinterpret this gesture as rude or dismissive, leading to an overreaction, when in fact they were simply swatting away a fly. This error stems from misreading the immediate context. Schema errors happen when your mental frameworks become too rigid or outdated. It's like using an old map that doesn't reflect recent road closures or new developments. For instance, if you have a schema that associates doctors with being male, you might be surprised or even dismissive when encountering a female doctor. This error arises from clinging to an outdated schema that doesn't reflect the reality of the world. Here's a key difference: context errors arise from misinterpreting the present situation, while schema errors arise from relying on outdated or inaccurate mental models. Both types of errors can lead to misunderstandings, misjudgments, and even harmful behaviors. However, by being aware of these potential pitfalls, we can strive to be more mindful of our interpretations, update our schemas with new information, and navigate the world with greater accuracy and understanding.

ReferenceYouTube

|

||