|

|

||

|

Consciousness remains one of the most elusive and intriguing subjects in the realms of philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience. It encompasses the awareness of one's environment, thoughts, emotions, and sensations, serving as the backdrop for human experience and identity. Consciousness is a concept that has fascinated and perplexed humanity for centuries and embodies the essence of our subjective experience and the ability to introspect. It encompasses the intricate tapestry of our awareness, allowing us to perceive and contemplate not only the world around us but also our own thoughts, emotions, and the very fact of our existence. It is the illuminating force that brings forth the richness of our inner lives and connects us to the external reality, shaping our understanding of ourselves and the universe we inhabit. Despite extensive study, the precise origins and mechanisms of consciousness continue to puzzle researchers, challenging our understanding of what it means to be sentient. As we delve into the depths of the human mind, consciousness serves not only as a subject of scientific inquiry but also as a profound centerpiece in discussions about what it means to be alive and self-aware.

What is Consciousness ?

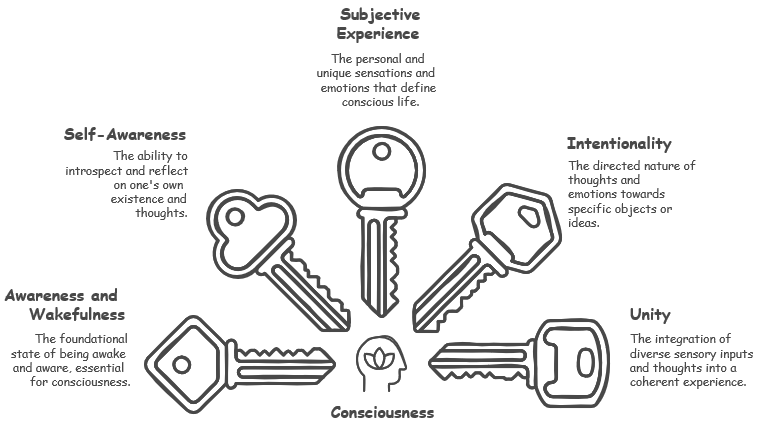

What are key aspects of Consciousness ?Consciousness involves several key aspects, each contributing uniquely to our understanding of mental awareness and self-perception. From the basic state of wakefulness to complex self-awareness, the subjective nature of experiences, the intentionality of thoughts, and the unity of cognitive processes, it is both intricate and profound. These dimensions not only define our interactions with the world but also pose significant questions about the neural and philosophical foundations of awareness. This exploration seeks to dissect these critical components, shedding light on the rich tapestry of consciousness and its pivotal role in human cognition.

Awareness and Wakefulness : the Foundation of ConsciousnessAt its core, consciousness can be understood as the state of being both awake and aware. This state fundamentally distinguishes us from periods of unconsciousness, such as during deep sleep or under the influence of general anesthesia. When we are awake and conscious, we are receptive to and actively process information from our internal and external environments. This encompasses sensory perceptions (sight, sound, touch, etc.), thoughts, emotions, and the subjective experience of "being." In essence, wakefulness and awareness provide the canvas upon which the rich tapestry of our conscious experiences is woven. It is through this dynamic interplay that we perceive, think, feel, and ultimately navigate the world around us. Illustrative ExamplesThese examples underscore the crucial role that wakefulness and awareness play in shaping our conscious experience. Without these fundamental elements, consciousness, as we understand it, ceases to exist.

Self-Awareness: The Mirror of the MindSelf-awareness signifies a profound level of consciousness wherein individuals transcend mere awareness and gain the ability to introspect – to turn their attention inwards and contemplate their own existence. This remarkable capacity enables us to not only experience thoughts, feelings, and sensations but also to reflect upon them, analyze their origins, and ponder their implications. It is akin to having an internal mirror that allows us to observe the workings of our own minds. In essence, self-awareness elevates consciousness to a new dimension, providing us with the remarkable capacity to examine our own mental landscape. It is through this introspective lens that we gain a deeper understanding of ourselves, our motivations, and our place in the world. Illustrative Examples

Subjective Experience: The Technicolor Symphony of the MindSubjective experience, often referred to as "qualia," forms the vibrant tapestry of our conscious existence. It encompasses the entirety of our personal, first-person perspectives, sensations, and emotions—the raw, unfiltered essence of what it feels like to be. These experiences are inherently private and unique to each individual, creating a kaleidoscope of consciousness that paints the world in countless shades of perception. In essence, subjective experiences, or qualia, represent the fundamental building blocks of our conscious lives. They are the brushstrokes that paint the canvas of our minds, creating a world of sensations, emotions, and perceptions that is both intimately personal and endlessly diverse. While the scientific study of consciousness seeks to understand the neural correlates of these experiences, their subjective nature remains a captivating mystery, reminding us of the profound depth and complexity of the human mind. Illustrative Examples:

Intentionality: The Compass of ConsciousnessIntentionality, often described as the "aboutness" of consciousness, denotes the directed nature of our mental states toward specific objects, ideas, or situations in the world. It highlights the essential characteristic of consciousness as being conscious of something. In other words, our awareness is not simply a passive reception of stimuli but rather an active engagement with the world around us and the contents of our own minds. In essence, intentionality serves as the compass of consciousness, guiding our attention, thoughts, emotions, and actions toward specific targets in the world or within our own minds. It underscores the dynamic and purposeful nature of consciousness, highlighting its role in enabling us to engage with, understand, and interact with the world around us. Illustrative Examples:

Unity: The Seamless Tapestry of ExperienceUnity refers to the remarkable capacity of consciousness to integrate a vast array of sensory inputs, thoughts, and emotions into a coherent and unified whole. Even though we are bombarded with a multitude of stimuli at any given moment—sights, sounds, smells, bodily sensations, internal monologues, and fleeting emotions—our conscious experience typically presents itself as a seamless and integrated stream rather than a disjointed collection of fragments. The question of how the brain achieves this remarkable feat of unifying disparate information into a coherent conscious experience is known as the "binding problem." While the precise mechanisms remain an area of active research, it is believed that various brain regions work in concert to integrate information from different sensory modalities and cognitive processes, creating a unified representation of the world and our place within it. In essence, the unity of consciousness highlights the remarkable capacity of the brain to create a seamless and integrated sense of self and world from a multitude of sensory inputs, thoughts, and emotions. This holistic experience enables us to navigate the complexities of our environment, engage in meaningful interactions, and make sense of the rich tapestry of our lives. Illustrative Examples:

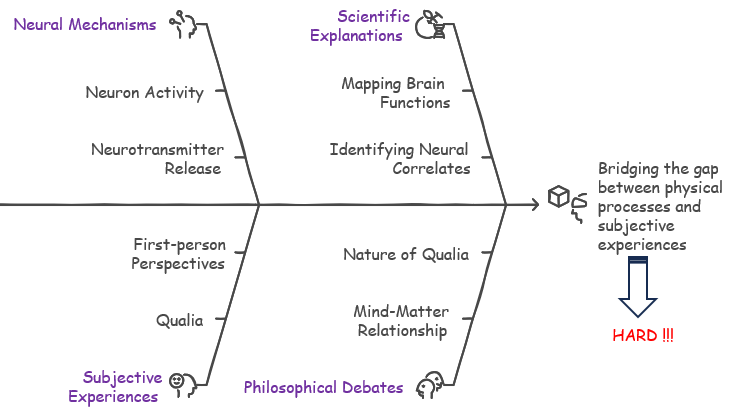

What is the "Hard Problem" ?The "hard problem" of consciousness, a term coined by philosopher David Chalmers, refers to the fundamental challenge of explaining how and why subjective experiences, or qualia, arise from physical processes in the brain.

It's the question of how we can bridge the gap between the objective, measurable world of neurons and neurotransmitters, and the subjective, private world of our inner experiences - the feeling of pain, the taste of chocolate, the redness of a sunset. In essence, the hard problem asks: Why and how does the brain's physical activity generate the "what it's like" aspect of consciousness? It's not just about explaining the mechanisms of information processing or the neural correlates of various mental states. It's about explaining why those processes and states are accompanied by subjective, first-person experiences. This problem is considered "hard" because it seems to defy traditional scientific explanations. We can describe in detail the neural pathways involved in pain perception, but that doesn't explain the subjective feeling of pain itself. We can identify brain regions active during visual perception, but that doesn't explain the qualia of seeing red or blue. The hard problem highlights a fundamental gap in our understanding of consciousness. While science has made remarkable progress in mapping the brain and understanding its functions, it still struggles to account for the subjective, qualitative aspects of our mental lives. This ongoing challenge continues to drive research and philosophical debate, pushing us to explore new ways of thinking about the relationship between mind and matter Why Research on Consciousness is hard ?Even though scientists and philosophers have spent ages trying to figure out consciousness, it's still a big mystery. We don't really know how it starts or what makes it work. This is why the research on consciousness is so hard - it's like trying to solve a puzzle without all the pieces. This makes it really hard to say exactly what it means to be alive and aware of yourself and the world. Again, this highlights the difficulty in studying consciousness - it's such a fundamental part of our being, yet it's so elusive. The human mind is an incredible thing, and consciousness is at the heart of it. It's what lets us have experiences, think about things, and understand ourselves. The more we learn about consciousness, the closer we get to understanding what makes us human and what makes life so special. But because it's so complex and intertwined with our very existence, researching consciousness is a constant challenge. It's like we're exploring a vast, uncharted territory within our own minds, and every discovery brings us a little closer to understanding the core of our existence.

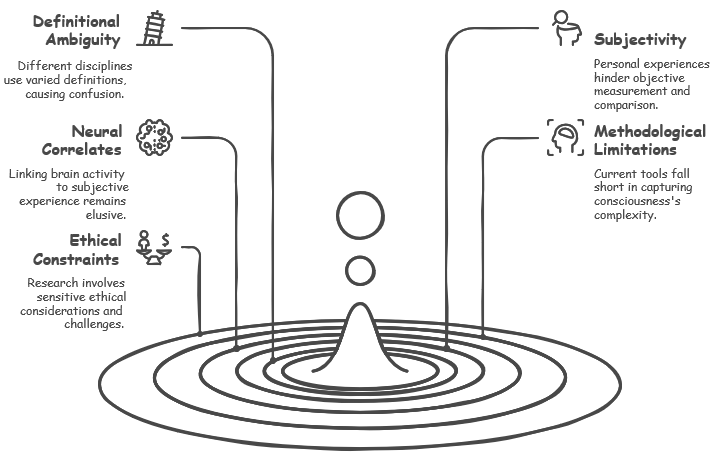

Definitional Ambiguity: A Tower of Babel in Consciousness ResearchOne of the major stumbling blocks in the study of consciousness is the absence of a clear and universally agreed-upon definition. The term "consciousness" is often used in a variety of ways, leading to confusion and miscommunication among researchers from different disciplines. This definitional ambiguity creates a "Tower of Babel" scenario, where scientists and philosophers may be talking past each other, hindering progress and collaboration.

This lack of a shared definition can lead to several challenges in consciousness research:

To address this challenge, it is crucial for researchers to be explicit about their definitions of consciousness and to strive for greater clarity and precision in their use of the term. Developing a shared conceptual framework and fostering interdisciplinary dialogue will be essential for overcoming the definitional ambiguity and advancing our understanding of this complex phenomenon. Subjectivity: The Private Realm of ConsciousnessOne of the most formidable challenges in consciousness research lies in its inherently subjective nature. Conscious experiences, such as the feeling of joy, the taste of chocolate, or the perception of a vibrant sunset, are fundamentally private and personal. They exist within the realm of the individual's first-person perspective and cannot be directly accessed or measured by external observers. This subjectivity poses a significant obstacle for scientific investigation, which traditionally relies on objective measurement, reproducibility, and the ability to verify findings through independent observation. When dealing with consciousness, researchers are confronted with the challenge of bridging the gap between the subjective, internal world of experience and the objective, external world of scientific measurement. Illustrative Examples:

The Challenge of Measurement:The subjective nature of consciousness makes it difficult to develop reliable and objective measures. Traditional scientific tools, such as brain imaging techniques or behavioral observations, can provide valuable insights into the neural correlates of consciousness and the outward manifestations of conscious states. However, they cannot directly access or quantify the subjective experience itself. To address this challenge, researchers are exploring innovative approaches, such as developing new subjective report measures, utilizing virtual reality to create controlled sensory environments, and exploring the potential of brain-computer interfaces to decode subjective experiences. In essence, the subjectivity of consciousness represents a fundamental challenge for scientific inquiry. However, it also serves as a constant reminder of the richness and complexity of the human experience, highlighting the unique and personal nature of our conscious lives. Neural Correlates: Bridging the Gap Between Mind and MatterWhile neuroscience has made significant strides in identifying neural correlates of consciousness (NCCs), or brain patterns associated with conscious states, a fundamental gap persists. We can observe and measure these neural activities, but we still struggle to grasp how they magically translate into the richness of our subjective experiences. This is the crux of the "hard problem" of consciousness, a term coined by philosopher David Chalmers, highlighting the perplexing challenge of explaining why and how physical processes in the brain give rise to the qualitative, first-person experiences we call consciousness. Examples of the Hard Problem:

Challenges for Research:This explanatory gap between neural activity and subjective experience presents a major challenge for consciousness research. It's like having a detailed map of a city but still not understanding what it's like to live there, to experience its unique atmosphere and culture. Some of the key challenges associated with the hard problem include:

Despite these challenges, the pursuit of understanding the neural correlates of consciousness and tackling the hard problem remains a central focus in consciousness research. New tools and technologies, such as brain-computer interfaces and advanced neuroimaging techniques, are opening up new avenues for exploration. While the hard problem continues to puzzle and intrigue, ongoing research is steadily shedding light on the intricate relationship between the brain and the mind, inching us closer to a deeper understanding of the enigmatic phenomenon of consciousness. Methodological Limitations: Peering Through a Fogged LensWhile modern science has equipped us with an impressive arsenal of research tools, such as brain imaging and electrophysiological monitoring, our ability to investigate the intricate processes underpinning consciousness remains limited. These tools, while invaluable for revealing neural correlates and activity patterns, often fall short when it comes to capturing the dynamic, high-level integration believed to be essential for generating subjective experiences. This methodological constraint resembles peering through a fogged lens, hindering our ability to grasp the full complexity of conscious phenomena. Limitations of Current Tools:

The Challenge of High-Level Integration:Consciousness is widely believed to arise from the dynamic and complex integration of information across various brain regions. Current tools are primarily designed to observe localized activity in specific areas, making it challenging to capture the large-scale, distributed patterns of neural interaction that may be critical for consciousness. To address these methodological limitations, researchers are actively developing new tools and techniques. These include:

Despite these challenges, ongoing methodological advancements and creative research approaches are steadily expanding our understanding of consciousness. By pushing the boundaries of what is currently possible, scientists are inching closer to unraveling the mysteries of the mind and revealing the neural mechanisms that give rise to the rich tapestry of our conscious experiences. Ethical and Practical Constraints: Navigating the Moral and Methodological MazeConsciousness research often treads on sensitive ethical ground, particularly when it involves human subjects. Studies involving individuals with severe neurological impairments, such as those in a coma or with disorders of consciousness, raise complex ethical considerations about consent, potential harm, and the ability to accurately assess subjective experiences. Additionally, animal studies, while sometimes used to explore the neural correlates of consciousness, are inherently limited by our inability to directly communicate with or fully comprehend the subjective experience of another species. These ethical and practical constraints create a challenging landscape for consciousness research, demanding careful navigation and constant vigilance to ensure the protection of both human and animal subjects. Ethical Considerations:

Practical Constraints:

Addressing these ethical and practical constraints requires ongoing dialogue and collaboration among researchers, ethicists, policymakers, and the public. Developing clear ethical guidelines, fostering open communication, and promoting responsible research practices are essential for navigating the moral and methodological maze of consciousness research. By balancing the pursuit of knowledge with the protection of human and animal subjects, we can ensure that consciousness research progresses in a responsible and ethical manner, contributing to our understanding of this fundamental aspect of human existence. Integrating Diverse Approaches: The Quest for a Unified FrameworkConsciousness, in its multifaceted nature, transcends the boundaries of any single discipline. Its investigation necessitates an interdisciplinary approach, drawing on insights from neuroscience, psychology, philosophy, computer science, and even fields like physics and mathematics. However, merging these diverse perspectives into a cohesive understanding of consciousness presents a significant challenge. Each field brings its own unique terminology, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks, making communication and collaboration across disciplines complex and demanding. Examples of Interdisciplinary Challenges:

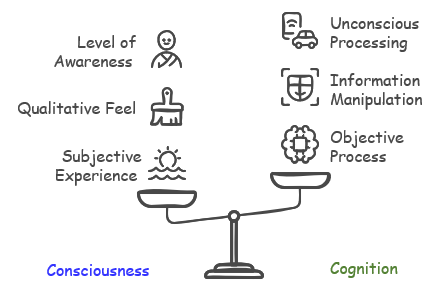

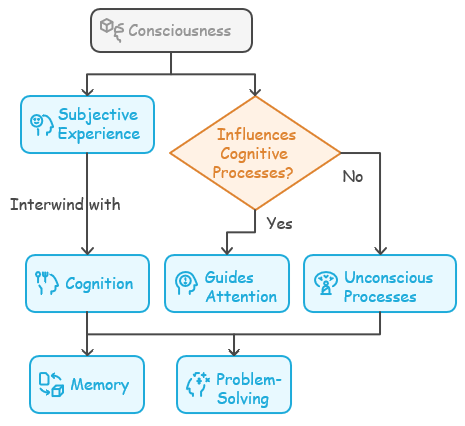

The Need for a Unified Framework:To achieve a comprehensive understanding of consciousness, it is crucial to integrate the insights and methodologies from various disciplines into a coherent framework. This requires overcoming the challenges of interdisciplinary communication and collaboration, developing a shared language and conceptual framework, and fostering a spirit of open-mindedness and mutual respect among researchers from different backgrounds. By embracing an interdisciplinary approach, consciousness studies can benefit from a synergistic exchange of knowledge and ideas. Neuroscientific findings can inform philosophical theories, while philosophical insights can guide the design of new experiments. Computational models can simulate neural processes and test theoretical predictions, while psychological studies can shed light on the behavioral and cognitive manifestations of conscious experience. The integration of diverse approaches offers the potential to overcome the limitations of any single discipline and create a more holistic and nuanced understanding of consciousness. While the journey towards a unified framework may be challenging, it holds the promise of unlocking the mysteries of the mind and revealing the true nature of this most fundamental aspect of human existence. How do you compare consciousness with cognition ?Consciousness and cognition, while interconnected and often intertwined, represent distinct aspects of the human mind. Understanding their relationship and differences is crucial in comprehending the complexities of our mental processes and the nature of subjective experience.

Key differencesConsciousness provides the subjective richness and meaning to our lives, while cognition provides the tools and processes that enable us to navigate and interact with the world. Together, they form the intricate tapestry of our mental lives, shaping our perceptions, thoughts, emotions, and actions.

Interconnectedness:While distinct, consciousness and cognition are deeply intertwined. Conscious awareness influences cognitive processes, guiding our attention, shaping our memories, and impacting our decision-making. Conversely, cognitive processes provide the content for conscious experience, generating thoughts, perceptions, and emotions that populate our conscious awareness.

Examples:

Can Studying General Anesthesia Help Us Understand How Consciousness Works?General anesthesia, a state of controlled unconsciousness, serves as a unique window into the intricate mechanisms of consciousness. While it doesn't provide a complete explanation of this enigmatic phenomenon, it offers valuable clues and research avenues by showcasing how consciousness can be systematically and reversibly altered. By carefully observing how different anesthetics disrupt or suspend various aspects of consciousness, scientists can deduce which neural activities and pathways are crucial for maintaining conscious awareness. This insight helps identify potential neural correlates of consciousness – specific brain patterns or processes associated with conscious states. In essence, general anesthesia acts like a controlled experiment on the brain, allowing researchers to observe the consequences of selectively dampening or interrupting neural activity. This provides a unique opportunity to pinpoint brain regions and networks critical for consciousness, as well as to investigate the specific neurochemical mechanisms involved. For instance, certain anesthetics disrupt communication between different brain regions, particularly those involved in integrating information from various sensory and cognitive domains. This suggests that the coordinated activity and information flow across these networks are vital for conscious experience. Other anesthetics may target specific neurotransmitter systems, further illuminating the molecular and cellular processes that underpin consciousness. Therefore, while general anesthesia doesn't provide a definitive answer to the "hard problem" of consciousness - explaining how subjective experience arises from physical processes in the brain - it serves as an invaluable tool for probing its underlying mechanisms. The insights gained from anesthesia research contribute to a growing body of knowledge about the neural correlates of consciousness, paving the way for a more comprehensive understanding of this fascinating phenomenon. Insights Gained from General Anesthesia:While it doesn't fully unravel the mystery of how subjective experience arises from brain activity, it provides valuable insights into the neural mechanisms that support conscious awareness. By observing how various anesthetics selectively disrupt or suspend different aspects of consciousness, researchers can glean crucial information about the brain regions, networks, and neurochemical processes vital for maintaining our conscious experience.

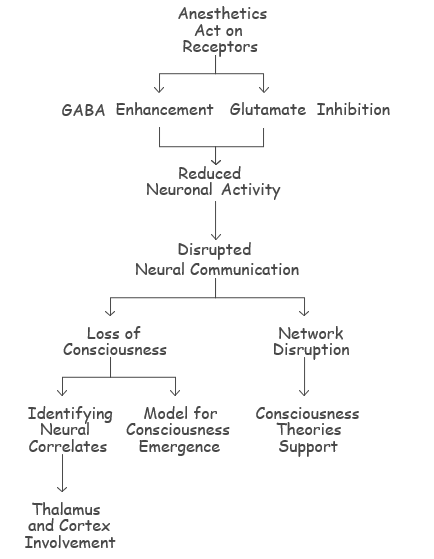

Mechanisms of General AnesthesiaAnesthetics act on specific receptors and neurotransmitters in the brain, suggesting that certain molecular and cellular processes are crucial for maintaining consciousness. Studying these mechanisms can shed light on the biochemical and physiological underpinnings of conscious states. They work by interfering with specific neurotransmitters in the brain, which are responsible for promoting wakefulness and processing sensory input. The most common targets are:

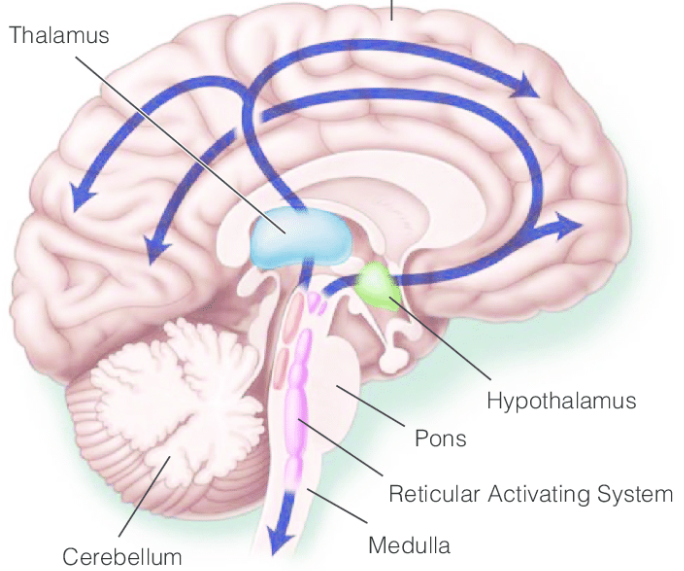

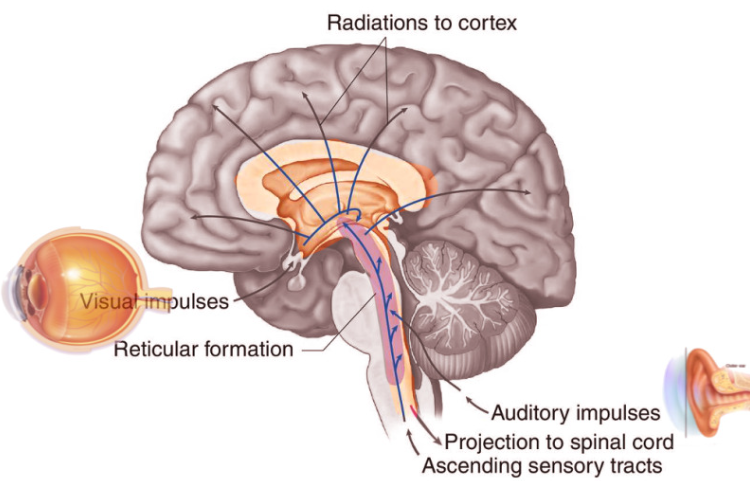

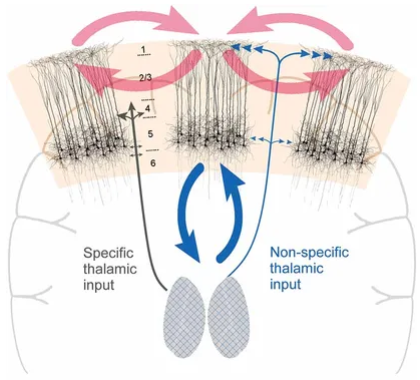

Neural CorrelatesGeneral anesthesia disrupts neural communication and information processing in the brain, leading to a loss of consciousness. Observing which brain regions and networks are affected by anesthesia can help identify potential neural correlates of consciousness, suggesting areas critical for generating conscious experience. In other words, It helps identify brain regions and pathways that are crucial for maintaining consciousness. For instance, effects on the thalamus and the cortex suggest their roles in the integrated information processing necessary for conscious experience. Network DisruptionAnesthetics disrupt the connectivity between different brain regions. Studies show that under anesthesia, the usual integration of information across the brain is compromised, supporting theories that consciousness depends on the widespread, integrated brain network activity. State TransitionsThe transition from wakefulness to unconsciousness under anesthesia resembles, in reverse, the natural transition from sleep to wakefulness, providing a model to study how consciousness emerges from neural activity. LimitationsWhile general anesthesia provides a useful model, it primarily shows how consciousness can be turned off or diminished, rather than explaining all the aspects of how it arises and functions naturally. Consciousness involves not only the activation or deactivation of certain brain areas but also a complex, dynamic interplay of neural circuits that support awareness, perception, and self-awareness. Complexity of ConsciousnessGeneral anesthesia affects various brain regions and networks simultaneously, making it challenging to pinpoint the precise neural mechanisms responsible for specific aspects of consciousness. Consciousness likely emerges from complex interactions among multiple brain systems, not just a single "on/off" switch. Individual VariabilityThe effects of anesthesia can vary among individuals, highlighting the complexity and individual differences in the neural underpinnings of consciousness. Lack of Subjective ReportsDuring general anesthesia, individuals are unable to provide subjective reports of their experiences, limiting our understanding of the qualitative aspects of consciousness and how they are affected by anesthesia. Unconsciousness and the Brain: Key Regions Where Dysfunction Causes Loss of ConsciousnessUnderstanding the intricate workings of the brain is crucial in deciphering the mysteries of consciousness. Certain regions of the brain are so vital that their dysfunction can lead to a complete loss of consciousness, plunging an individual into a state of unconsciousness or even a coma. Let's explores the critical brain regions responsible for maintaining our awareness and how their malfunction can disrupt this delicate balance, shedding light on the neurological foundations of consciousness and unconsciousness. Reticular Activating System (RAS)This network of neurons located in the brainstem is crucial for maintaining wakefulness and alertness. It regulates the sleep-wake cycle and arousal. Damage to the RAS, often due to traumatic brain injury, stroke, or other forms of brainstem damage, can result in a coma or persistent unconsciousness. The RAS receives input from various sensory systems, such as the eyes, ears, and skin, and sends signals to the thalamus and cortex. This process helps to filter and prioritize incoming information, allowing the brain to focus on relevant stimuli while ignoring irrelevant ones. The RAS also plays a role in regulating the sleep-wake cycle, by modulating the activity of various neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and serotonin.

Image Source : ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice critical care

Image Source : Neuroanatomy, Reticular Formation ThalamusThe thalamus acts as a relay station for sensory and motor signals to the cerebral cortex and plays a vital role in consciousness and awareness. Damage to the thalamus, particularly to the intralaminar nuclei, can impair consciousness and even result in coma. The thalamus serves as a critical hub in the brain's network, linking sensory processing with the regulation of consciousness. Dysfunction in the thalamus disrupts these vital connections, leading to a breakdown in communication within the brain's cortical regions. This disruption can manifest as unconsciousness, highlighting the thalamus's essential role in maintaining a conscious state.

Image Source : Coupling the State and Contents of Consciousness The above highlights the critical role of the thalamus in maintaining consciousness by facilitating communication between different cortical regions. To focus on how dysfunction in the thalamus can lead to unconsciousness

BrainstemBeyond the Reticular Activating System (RAS), the brainstem as a whole plays a critical role in maintaining life-sustaining functions that are essential for survival and consciousness. The brainstem, which includes the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata, is responsible for regulating fundamental processes such as heart rate, breathing, and the sleep-wake cycle. These regions of the brainstem also facilitate communication between the spinal cord and higher brain regions, ensuring that sensory and motor signals are properly relayed. Damage to the midbrain, which is involved in functions such as visual and auditory processing, motor control, and the regulation of arousal, can severely disrupt these processes. When the midbrain is compromised, the ability to maintain consciousness can be affected, potentially leading to states of altered consciousness, unconsciousness, or even coma. Similarly, the pons, located below the midbrain, is crucial for controlling respiratory rhythms, regulating sleep, and serving as a bridge between different parts of the nervous system. Damage to the pons can interrupt these vital functions, particularly the regulation of breathing, which is critical for life. Such damage can also impair the transmission of signals between the cerebrum and the cerebellum, further contributing to the loss of consciousness. Overall, the brainstem's integrity is paramount for sustaining consciousness and life itself. Any significant damage to these areas, whether due to stroke, trauma, or disease, can lead to profound neurological deficits, including unconsciousness or coma, highlighting the brainstem's indispensable role in maintaining the body's most fundamental functions. Cerebral CortexWhile the cerebral cortex is primarily responsible for higher cognitive functions such as thinking, reasoning, memory, language, and sensory perception, it also plays a crucial role in maintaining consciousness and awareness of the external world. The cerebral cortex is the outermost layer of the brain, comprising a complex network of neurons that integrate and process information from various sensory modalities, allowing us to interact meaningfully with our environment. Widespread damage to both hemispheres of the cerebral cortex can severely disrupt these essential functions, leading to a profound loss of consciousness. When the cortex is compromised on a large scale, the brain's ability to process sensory information, execute motor functions, and maintain a coherent sense of self and awareness is significantly impaired. This type of extensive cortical damage often results in a state of unconsciousness, where the individual is no longer able to perceive, respond to, or interact with their surroundings. Such widespread cortical damage is often observed in cases of diffuse axonal injury (DAI), a type of traumatic brain injury where the brain's long connecting nerve fibers (axons) are sheared or torn due to rapid acceleration or deceleration forces, such as those experienced during car accidents or falls. DAI typically results in widespread disruption of neural communication across the cerebral cortex, leading to immediate and prolonged unconsciousness, often manifesting as a coma. Similarly, severe global ischemia, which occurs when the brain is deprived of adequate blood flow and oxygen for an extended period, can also lead to extensive cortical damage. This condition is often the result of cardiac arrest, severe hypotension, or other medical emergencies that cause a significant reduction in cerebral blood flow. Without sufficient oxygen, neurons in the cerebral cortex begin to die off, leading to widespread brain damage. The loss of cortical function in such cases can result in a persistent vegetative state, where the individual loses consciousness and awareness, yet may still retain some autonomic functions controlled by lower brain structures. Reference

YouTube

|

||